Steward of the Keys: Angela Sayre, Founder of Crustacean Plantation, Saves Hermit Crabs

Author: Laura Myers, November 2025

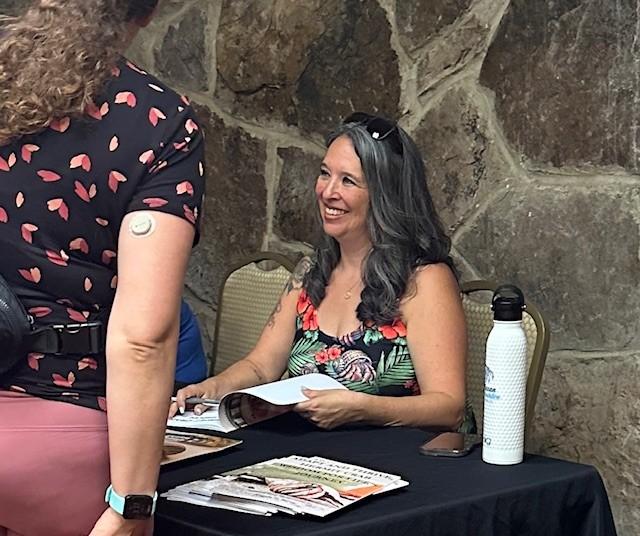

Angela Sayre, a privacy-tech guru in Tavernier, is known as the “Jane Goodall of hermit crabs” and as “CrabberaTeresa” among friends as executive director of Crustacean Plantation Inc., her nonprofit dedicated to the conservation of wild Florida Keys hermit crabs.

Hermit crabs, as small crustaceans, do not grow their own shells but live in abandoned shells, sometimes from sea snails, or those on a beach. The Keys are home to only one species of land hermit crab that lives on land close to water, Sayre said.

Sayre estimates she’s scattered more than 25,000 empty shells throughout the Keys and around her Upper Keys home, named Crustacean Plantation. Her organization receives a box of empty shells nearly every day — from far-flung Alaska, Australia, Canada, England and Korea and throughout the country.

Hermit crabs also can live up to 50 years, show characteristics of intelligence, are fighters that create societal castes, can lay more than 10,000 eggs in the ocean, and as they grow, require larger shells for protection to survive.

“Hermit crabs are scavengers; they eat everything,” Sayre said. “They serve an ecological purpose as nature’s little janitors, returning nutrients to the soil as they move around, aerating debris and plant matter. Some will only move into a certain color of shells. Their eyes are so soulful.”

Sayre and husband Brian, natives of Jackson, Ohio, are parents of three children in their 20s and own the property, described as the “perfect hermit highway,” located on Canal Street near Harry Harris Park.

The homestead was once part a 143-acre pineapple plantation owned by the Johnson pioneering family in the Upper Keys community, known as Planter, in the mid-1800s.

Decades ago, Keys residents could hear the frequent nightly sound of thousands of hermit crabs scurrying about in nature. “Their populations are depleting and have been depleting over the years,” Sayre said.

That depletion is due to property development and likely began in the 1970s, when people gathered hermit crabs to sell as take-home souvenir pets. Newspaper headlines, collected by Sayre from that era, declared “3,000 hermit crabs a day are being collected off Keys for novelty pet” and “Will hermit crabs replace banned turtles as pets?”

Former Summerland Key resident Shelley Burns, now a Maryland resident who’s in her mid-60s, recalled collecting Lower Keys hermit crabs in 100-pound burlap bags as a pre-teen and driving up to Miami with her parents to sell them for medical research.

“We collected them in 5-gallon buckets with a can of cat food,” Burns said. “As a kid, it was fun. I would try to keep the biggest one as a pet. Back then, you tried to live off the land.”

Burns stumbled on Sayre’s organization through Facebook and contacted Sayre to pledge her support.

Cedar Rapids, Iowa resident Blade Mullinex — once an avid hermit crab pet collector and former pet store employee who now constructs koi ponds throughout his landlocked home state — also collected thousands of sea shells, stored in 5-gallon buckets, from shuttered pet stores.

He, too, discovered Sayre and Crustacean Plantation online and today frequently ships boxes of shells to Tavernier. Mullinex and Sayre met up in Chicago recently with their families to discuss their passion to preserve hermit crabs.

Today, Sayre’s work — through her organization that’s believed to be the only one of its kind in the United States — includes documenting and marking every donated shell with initials and date received from a donor. “I track how far the shells are traveling.”

Hermit crabs can still be purchased in the Keys, as there are limited federal and state regulations protecting the creatures in the U.S. By contrast, in Japan, hermit crabs are protected by law and classified as “national natural monuments” because of their scientific and cultural value.

Sayre, the director of compliance for the digital privacy start-up technology company Cloaked, works remotely from the Keys.

She’s also the author of two books: “Hermit Crab Wisdom: Little Lessons for Big Hearts” and “Adapt and Thrive: Hermit Crab Wisdom for Life’s Journey,” and sells them online to support Crustacean Plantation.

“I would like this work to outlive me,” Sayre said. “I would like to see this, through education and conservation, as my legacy. This is my contribution to the Keys eco-system, to restore something most people aren’t even aware of.”

Keys Traveler: When did you first come to the Florida Keys and why?

Angela Sayre: In March of 2019. Our middle child was stationed in Islamorada with the Coast Guard, and after helping him settle in, we decided to make the Keys our home too.

KT: What aspects of the Keys environment or way of life matter most to you?

AS: Moving here meant discovering an entirely new world of plants and animals. Up north we were used to deer, turkeys, and squirrels. In the Keys, we found ourselves stepping around tiny anoles, big iguanas, discovering land hermit crabs and learning all about native plants like wild lime, lignum vitae, and bromeliads. Preserving the Keys’ beauty and understanding the wildlife that belong here quickly became a top priority for us. We showcase our native landscape and natural “crabitats.”

KT: What inspired you to become passionate about protecting the Keys’ natural world and how does that passion impact your daily life and work?

AS: My inspiration came from discovering our Coenobita Clypeatus, the hermit crab species living on land but close to water. The Keys have only one species of land hermit crab, and finding them around our home was eye-opening. They became the foundation of my passion to speak up for the natural world of the Keys.

KT: How do you personally work to ‘connect and protect’ the Keys’ environment and the island chain’s unique lifestyle?

AS: I quickly realized that the challenges I saw in my neighborhood were the same ones hermit crabs face throughout the Keys and the world. I share their stories to raise awareness, especially about the growing problem of hermit crabs being forced to wear trash instead of shells. Finding a shell on the beach may feel like a special treasure for a person, but for a hermit crab it means a safe home and a better chance of survival. I’ve partnered with local state parks to host workshops, and I set up tents at community events, summer camps, and schools to teach families and kids about hermit crabs. Every person I reach has the potential to spread that awareness, and that ripple effect is how real change happens.

KT: What do you hope your environmental actions in the Keys will help to accomplish?

AS: To inspire residents and visitors to rethink their relationship with shells. Instead of taking them home as souvenirs, I want people to leave them in place so hermit crabs can use them as the homes they desperately need. Our motto is “Leave the Shell, Take the Memory.” shell left behind makes a difference in helping them survive. Hermit crabs are much more than a curiosity along our shorelines. Their movements help new plants take root, and when they dig down to rest or molt, they naturally aerate the ground. I hope others can see how protecting hermit crabs helps protect the balance of the Keys’ ecosystem.